The long-horned beetle, Tetraopes tetraophthalmus, here feeding on milkweed flower buds, 6-15-18, probably out-numbers the monarchs in your local milkweed patch.

The milkweed flowering season has peaked now — for common milkweed, at least — and will fade to a close over the next few weeks. By mid-July or so all those butterflies, moths, bees, wasps, ants, soldier beetles, and flower flies attracted by milkweed nectar will have drifted off to different blooming plants and generally become harder to find.

If that dispersal seems like a bummer to you, you may want to take a look at Monarchs & Milkweeds (Princeton University Press, 2017) by Anurag Agrawal for a pick-me-up and change of perspective.

Agrawal barely mentions the dozens of nectarers that use milkweeds only for sugar hits. Some (fewer than you might guess) are important participants in the lives of these plants because they pollinate them. But most of the insects that draw our eyes to the milkweeds each June and July are more or less irrelevant to their ecology.

In Chapter Seven, “The Milkweed Village” he focuses on ten other insects as dependent on Asclepias as monarchs are. All have evolved adaptations that enable them to feed on plants whose toxins repel virtually all other herbivores. Several of the group are, like the monarch, brightly colored and distasteful to most predators. Also like the monarch, all have developed features, behaviors, and a general ecology so intertwined with Asclepias that they cannot survive without it: they are milkweed obligates.

That “Milkweed Village” chapter, especially Agrawal’s colorful chart (p. 171) detailing the seasonal sequence of those eleven insects from spring through fall inspired Jesse and me to start a focused exploration of our backyard milkweeds last May. How many of Agrawal’s cast of characters could we find in our own milkweed village? How would their seasonality in a South Jersey yard compare to his sequence in central New York State? And could we find any Asclepias specialists that he does not mention?

Two other sources proved as useful as Monarchs & Milkweeds:

“The Story of an Organism: Common Milkweed” by Craig Holdrege (2010) available at The Nature Institute:

Nature Institute The Story of an Organism Milkweed

Milkweeds, Monarchs, & More: A Field Guide To the Invertebrate Community in the Milkweed Patch (2nd Edition, Bas Relief Publishing, 2010) by Ba Rea, Karen Obenhauser, and Michael Quinn.

Monarch caterpillar, presumably a grandchild of the Mexican over-winterers, 6-10-18.

Three Slightly Different Lists:

The eleven “Village” species described by Agrawal (abbreviated as AA below) include two leps (monarch and milkweed tussock moth), three beetles, two true bugs, one leaf-mining fly, and three aphids that he and his students have studied in central New York. (He is an entomologist at Cornell).

Craig Holdredge (CH below) focuses more on Asclepias syriaca than the insects it draws, and his detailed account of the sequence of flowering, the complexities of pollination, the formation and dispersal of seeds, and much else is sure to deepen your appreciation of this amazing plant. He turns to the insects in the last third of his article and his one-page list of “Milkweed-Specific Herbivores” (p. 17) may be the most useful quick guide to the group that you can find in any of these three sources. Print it out and you can start your own search for these insects a.s.a.p. He details ten species for upstate New York, leaving out two of the aphids on AA’s list but including a third lep: the dogbane tiger moth.

Rea, Obenhauser, and Quinn (ROQ below) have compiled a guide to milkweeds and insects throughout North America – not just the milkweed obligates but also nectarers, predators, parasites, scavengers, and passers-by. It is a rich compilation, but the three authors do not intend the book to be comprehensive. It would probably be impossible just to describe the multiple hundreds (thousands?) of species that nectar on milkweeds from New Jersey to California. Still, ROQ’s photos and short descriptions are extremely helpful to anyone trying to study a milkweed patch’s activity. They identify fourteen milkweed specialists in North America: seven leps (adding four southern species to AA’s and CH’s lists – queen, soldier, tiger-mimic queen, and a Pyralid moth), the three beetles and two true bugs AA and CH both list, one of AA’s three aphids, and they add a western beetle, Chrysochus cobaltinus, the blue milkweed beetle.

ROQ hint at another possible specialist with four small photos and two intriguing sentences (but no cited reference) on page 38: “These planthoppers were observed feeding exclusively on milkweed in southeastern Pennsylvania. The nymphs fed in groups of three to six individuals and began emerging as adults in late July.” The species (one of fifty-eight in the family Flatidae) is not named, apparently because distinctions in that group are so subtle.

Our Yard’s Milkweeds:

Our yard holds two swamp milkweeds (A. incarnata) in the garden; about a dozen individual butterfly-weed plants (A. tuberosa) scattered around the sunniest spots of the yard; and three or four stands of common milkweed (A. syriaca) comprising about a hundred shoots in total that grow each year in and around a mostly-untended section near our compost bins and flat-bed trailer.

The common milkweeds draw the most diversity by far. We have not yet found any milkweed obligate feeding on either of the other two species that has not also appeared on our A. syriaca.

Common milkweeds in our yard, perhaps a single clone, 6-30-19.

A Guide To the Villagers:

The first five species below sequester the cardiac glycosides they ingest from the milkweeds (i.e. store the toxins in their bodies) and so are poisonous to birds and most other predators. Those five plus the swamp milkweed beetle, which apparently does not sequester milkweed toxins, are also brightly colored and conspicuous — to warn potential predators of their identities. These “aposematic” colors help make all six easy to identify.

Those six species and the others below are arranged from those easiest to find to those that require more focused searches. All photos come from our backyard in Port Republic either last year (2018) or this (2019).

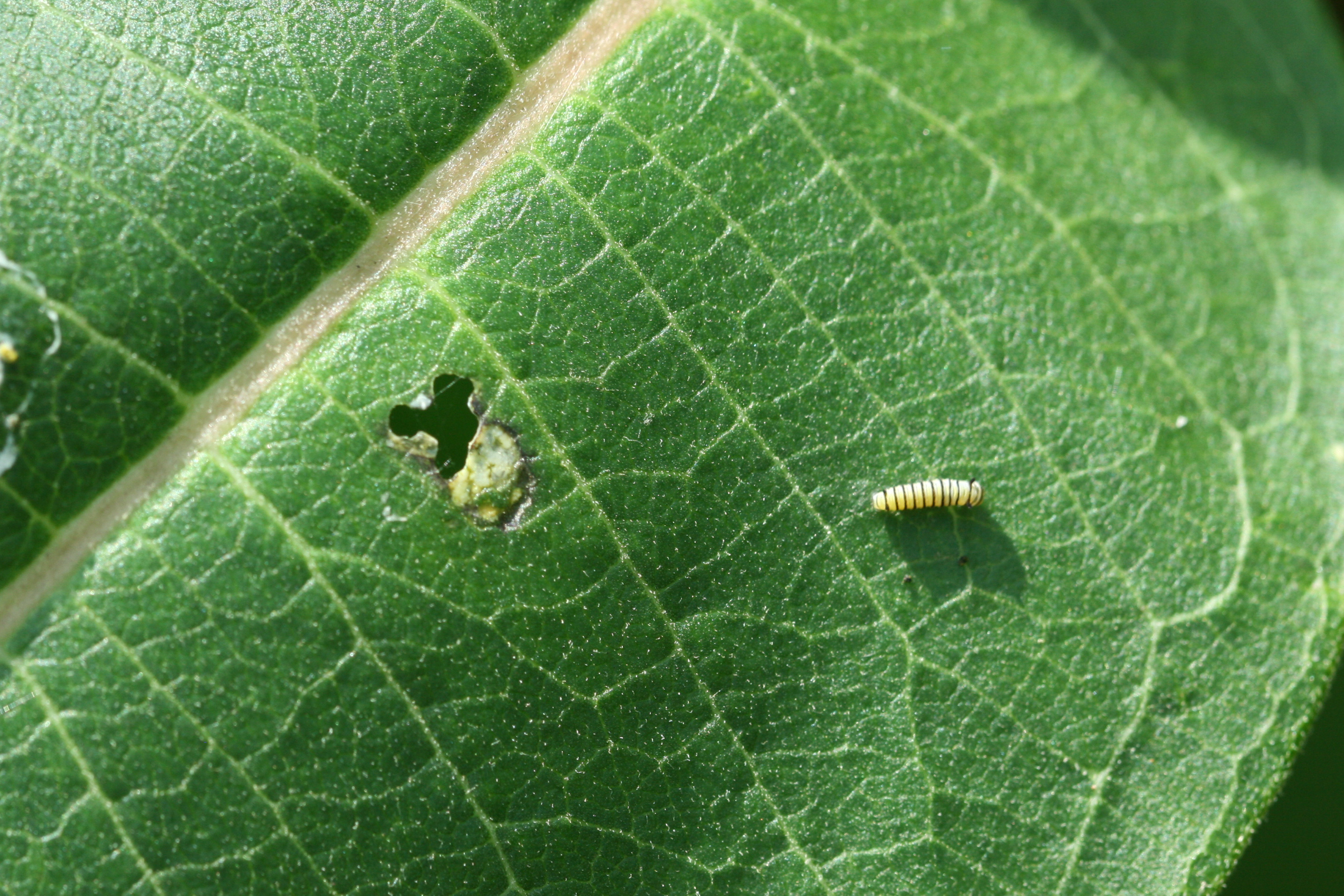

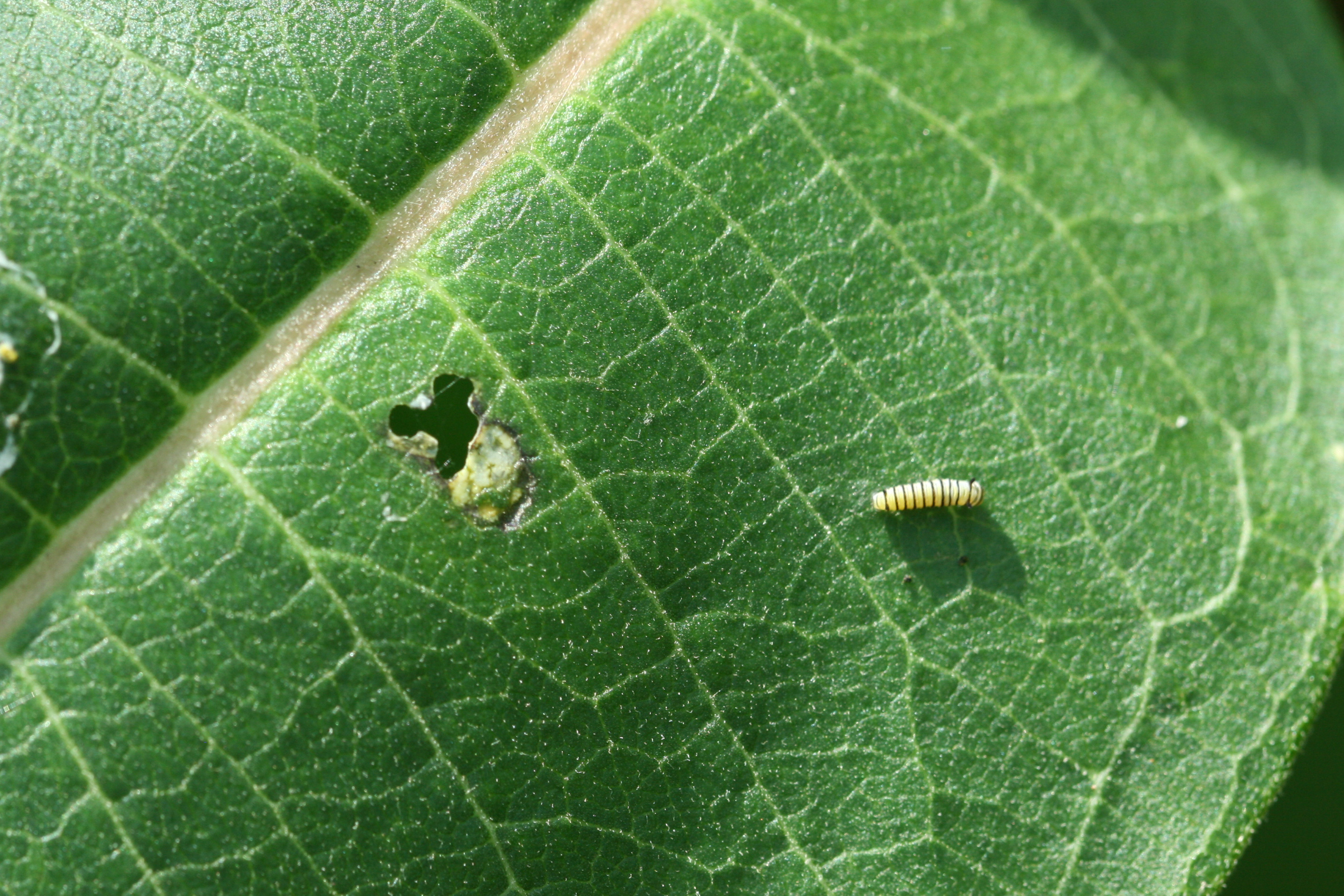

Young monarch caterpillar leaving a trench it created, 8-12-18.

Monarch, Danaus plexippus: No reader of this post needs help identifying North America’s most celebrated insect, but if you take up Agrawal’s book, you may be surprised how much you will learn that you did not know. One of AA’s points is evident above: monarchs are not immune to milkweed toxins and early in-star cats are especially vulnerable. Young cats can even be drowned by exuding latex. They usually feed by “trenching,” as AA calls it — cutting a hole in leaf while carefully avoiding the larger veins as they chew and so minimizing the milkweed’s defensive gushes of latex.

AA notes that, beginning in the 4th instar, monarch caterpillars often notch large leaves at the base of the petiole. “Like digging a circle trench, this may take tens of minutes…cutting, retreating, and wiping away the latex. [Finally] the caterpillar feeds in the absence of the flowing latex.” Photo 6-8-18.

Long-horned milkweed beetles, as they can be frequently found: the female chews on common milkweed while the male mates with her, 7-19-18.

Long-horned Milkweed Beetle (a.k.a. red milkweed beetle), Tetraopes tetraophthalmus: Of all the local milkweed specialists, this pretty creature is the easiest to ID and to photo — generally walking around the plants slowly and boldly and flying only short distances. Adults emerge in early June (late May?) even before milkweed blooms to feed on both leaves and unopened flower buds — but only on A. syriaca. It may be the most specialized member of the Village, limited entirely to common milkweed. Tetraopes means “four-eyed,” a feature evident in the photo at the top of the post, one pair of eyes above the antennae and another pair below. Last year we still had numbers in our yard nearly to the end of July. So far, they are even more numerous this year.

Small milkweed bug nectaring on common milkweed, 6-17-18.

Small Milkweed Bug (Lygaeus kalmii): This is the first of the two milkweed look-alike “seed bugs” that both emerge in June. Adults of this species appeared both last year and this year just as the first common milkweed flowers opened in our yard — around June 10th — and were still present until late August. AA suggests this species and the large milkweed bug feed on seeds alone; CH lists L. kalmii’s primary food as “sap of common milkweed” and notes it is “not a narrow specialist”; ROQ note small milkweed bugs can act “as scavengers and predators…especially in the spring when milkweed seeds, their preferred food, are scarce or non-existent.” ROQ add, “L. kalmii‘s ability to cope with milkweed toxins enables them to prey on other milkweed specific organisms. They have been documented eating each other.”

Young small milkweed bugs cannibalizing one of their own, 8-7-18. This feeding continued for ten minutes plus.

Large milkweed bug nectaring on common milkweed, 6-24-19.

Large Milkweed Bug, Oncopelius fasciatus: AA and CH agree that the second milkweed bug of the year is a seed specialist. ROQ note that it consumes “milkweed plant matter, mature and maturing milkweed seeds, and nectar from milkweed and other flowers.” In our yard, it has emerged both years for the first time on the same date, June 17, three or more weeks before the earliest seed pods appear. The only feeding that we have witnessed so far during that period is nectaring. It does climb up onto the seedpods as soon as they form, and by September it is easily the most numerously visible of all the milkweed obligates.

The adult’s thick black bar running across the wings distinguishes this species from its look-alike seed bug. (L. kalmii shows an orange X across its back.) 8-1-18.

A common scene in fall: clusters of large milkweed bugs huddled together on milkweed leaves, perhaps to maximize their chances of being identified by birds as poisonous (?). 10-16-18.

Milkweed tussock moth caterpillars, 8-24-18.

Milkweed Tussock Moth, Euchaetias egle: Here’s a creature most butterflyers and milkweed growers know, and some dislike. It is the last of the obligates to make itself visible each year, appearing in the caterpillar stage in mid- to late-summer (adults are entirely nocturnal). They seem to come just when most of the milkweed leaves in your yard are looking bedraggled and ready to drop to the ground — and in big years they can land a kind of “death-blow” to the last of Asclepias‘s greenery. I think that’s the reason it is sometimes considered a “pest.” But does it do more total damage to milkweed leaves than monarchs do? It doesn’t migrate to Mexico, of course, but it is a native species and needs milkweeds for the same reasons the monarch does.

ROQ note the bright warning colors of the late instar have led to the alternate name, “harlequin caterpillar.” The two cats in the photo were our first last year and we saw only a few afterwards — perhaps a consequence of 2018’s tough weather that apparently limited the numbers of many leps.

Swamp milkweed beetle on swamp milkweed stalk, 6-8-18.

Swamp Milkweed Beetle, Labidomera clivicolis: AA charts this pretty beetle among the earliest of the obligates to appear in his area and the story seems the same in South Jersey. We saw the first of the year in our yard in late May in both 2018 and 2019, including two mating on 5-31-18. Like mourning cloaks and angle-wings, they over-winter as adults, often [according to ROQ] “in the shriveled , wooly leaves of mullein plants.” Apparently, they prefer to feed on swamp milkweed in the wild, hence the name. In our yard they consume the leaves of both A. incarnata and A. syriaca. Larvae appeared in June in 2018 and the second brood adults were present into August.

Swamp milkweed leaf showing apparent beetle damage, 6-4-18. Like other milkweed feeders, L. clivicolis avoids the larger veins.

Swamp milkweed beetle walking the edge of common milkweed, a frequent activity, 6-24-19.

Milkweed weevil in what seems a typical spot for late-spring brood – in shade under common milkweed leaves, 6-24-19.

Milkweed Weevil, Rhyssomatus lineaticollis: If you are still following this compilation (is anyone out there?), we have now reached the point when searching and finding grows tougher. CH calls this creature the seed weevil, although he lists its primary food as “the pith of common milkweed stems.” AA calls it the milkweed stem weevil, although he notes it feeds “on stems in the spring and seedpods in the fall,” charts it in two different seasons, late May to late June (stem-eating) and mid-August to mid-September (seed-eating), and hints that it might be two separate species. ROQ’s simpler name, the milkweed weevil, may be best. In our yard it seems easier to find later in the summer, after seedpods appear. To find the earlier brood you need to turn over leaves, especially low on the plants, or look deep into the flower clusters.

Larval milkweed weevil. Note flow of latex created by this or another milkweed feeder. 7-19-18.

Adult milkweed weevil of second brood feeding in the open on top of common milkweed leaf, 7-19-18.

Oleander aphids on common milkweeds, 8-7-18.

Aphids, Aphis, sp.: The milkweeds and aphids story seems complicated. AA lists three species feeding on his milkweeds; CH lists only the milkweed aphid, Aphis asclepiades as a milkweed-specific herbivore; and ROQ, despite the continent-wide breadth of their book, name and illustrate only one, the species above, the oleander aphid, Aphis nerii. So far that is the only species we have been able to find.

AA spends several pages detailing the ecology of the three species he considers. Among other things, he points out this is another case where an insect that seems a pest might not be a bad as many of us presume. One researcher in AA’s lab found that monarch caterpillars growth was enhanced when they fed on leaves previously fed on by aphids.

Dogbane tiger moth under common milkweed leaf, 6-8-18.

Dogbane Tiger Moth (a.k.a. Delicate Cycnia), Cycnia tenera: AA does not mention this beauty, perhaps because milkweed may not to be its primary food. CH and ROQ both include it on their lists, noting it feeds on milkweed as well as dogbane. According to CH, it sequesters cardiac glycosides (also available in dogbane). He considers the adult “cryptic” and the caterpillar “aposematic.” We found the adult above early one morning at the beginning of our little project, but have not seen an adult since (a black light might end that problem). We found our first caterpillar just last week.

Dogbane tiger moth caterpillar on common milkweed, 6-25-19.

Dogbane beetle on common milkweed, 8-1-18.

Dogbane Beetle, Chrysochus auratus: This gorgeous creature makes none of the lists I’ve been citing here, but BugGuide notes that, although dogbane seems its primary food, it is “also reported in association with common milkweed.” In our yard it regularly explores common milkweed — flying back and forth from nearby dogbane plants. And we have once or twice seen it apparently eating Asclepias syriaca. At the moment, it is far more numerous in our yard than it was during any period in 2018, so I am hoping to document that consumption more certainly. All sources seem to agree it sequesters cardiac glycosides and shows aposematic colors to warn predators away. It is too pretty not to keep on the list!

Dogbane beetle apparently feeding on common milkweed, 7-29-19.

Planthoppers apparently feeding on common milkweed, 6-25-18. (The waxy threads are a defensive feature.)

Planthoppers, Flatidae, sp: Our yard list ends with this might-have-been. These larvae seemed to be feeding on our common milkweed, and they look like those in the photos of the planthopper larvae ROQ describe as “feeding exclusively on milkweed in southeastern Pennsylvania,” and suggest might be a milkweed specialist not yet recognized (p. 38). We did not find the adults last year and have not yet found the larvae this year….yet!

Final Words:

We would very much like to hear from anyone who has surveyed their plants for these or other milkweed obligates — and from anyone who takes up the chase now. Corrections are also welcome.

Best of luck to all explorers!

Sincerely,

Jack Connor

PS: For more from Anurag Agrawal and his monarch and milkweeds adventures, you can go to his website:

Anurag Agrawal at Cornell University