Source: Wikipedia

Biographical Information

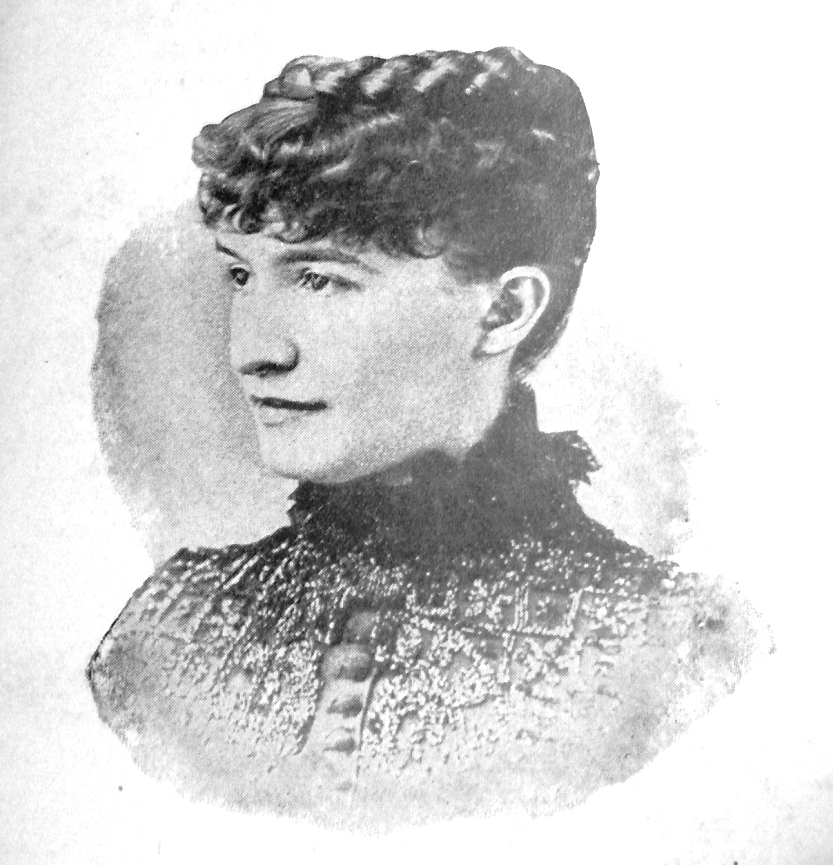

Born in 1850 to parents William Law Murfree and Fanny Priscilla (Dickinson), Mary Noailles Murfree spent much of her childhood in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. At the age of four, Murfree was struck with a sickness that left her with a minor paralysis, causing her to limp. In response to her physical impairments, Murfree began to read avidly. At the age of five, Murfree took a trip to the Tennessee mountains with her family, a trip that the Murfrees made a tradition in the following years (Gehrman 318). Murfree eventually developed an infatuation with both the people and the geography of the Appalachian region of the south. This ultimately lead the writer to establish an acute literary style that realistically depicts the language and culture of the Appalachian people, making Murfree one of the most notable authors of the American local-color movement (Gehrman 319).

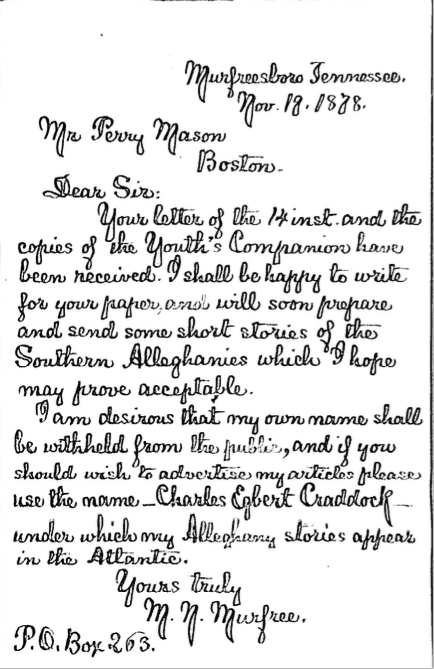

Mary N. Murfree, or “Charles Egbert Craddock,” was perhaps one of the most notable local-color women writers of the nineteenth century (Pryse 591). Until about ten years before Murfree’s “The Mystery of Witch-Face Mountain commenced publication, the author maintained her pseudonym. Throughout her lifetime, Murfree also wrote a few historical fiction novels but is most remembered for her literary significance in the local-color genre. Pryse notes that Murfree as a southern local-colorist was distinct from her New England counterparts because of her depiction of “class differences” (591). Despite growing as both a woman and a writer during the tumult of the US civil war, Murfree developed a significantly successful professional career as an author and, considering the laborious research of her work, as arguably both a historian and anthropologist.

Photo source: Murfree, Mary Noailles, “Papers of Mary Noailles Murfree,” 1878, Special Collections Research Center, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA.

“The Mystery of Witch-Face Mountain”

Murfree was most famous for her short stories, one of which is “The Mystery of Witch-Face Mountain.” Serialized in the Atlantic Monthly, the story first appeared in the September 1895 issue, and later in the short story collection The Mystery of Witch-Face Mountain and Other Stories, which Murfree collected herself.

The physical setting in Murfree’s short story depicts a small town near what mountaineers call the Witch-Face Mountain. Throughout the story, the mountain’s ill-omened witch-face is illustrated as a mocking foreshadowing of impending doom. Concerning the building of an overpass through the town, the plot illustrates the conflicting views of characters with different backgrounds and political interests.

Though a number of significant characters are mentioned, the story’s young female character becomes the most significant. The story follows the young mountaineer Narcissa Hanway (who is actually absent at the beginning of the story) throughout a controversial debate about the building of an overpass across the mountain—predominantly of interest to the strangers, and of disinterest to the mountaineers. A jury of men, who collectively display a severe distaste to Narcissa’s presence at meetings of such “public” matters, ultimately deliberate the decision. Though Narcissa is significantly averse to the building of the overpass, her decision essentially goes unaccounted-for. When the overpass, which eventually falls into disuse, is built blocking the mountain, Narcissa reflects somberly on the mountain’s former beauty and dimmed mystery.

Criticism

Murfree depicted most of her characters and plot over a backdrop of elaborately curated images, which as Gehrman suggests, seems to have been Murfree’s largest flaw regarding the author’s critical reception. Critics began to increasingly scrutinize Murfree’s elaborate descriptions of landscape, claiming them to be distracting and repetitive. Pattee even claims that, having analyzed a few depictions of setting, most of them are “painted lavishly with adjectives, and presented with impressionistic rather than realist effect,” eventually asserting that the “scenery dominates the book” (311).

Some critics grew tired of Murfree’s aesthetic, but other critics praised Murfree’s style, as it seemingly borrowed the Gothic trope of elaborate landscapes, to convey characters’ epistemological, emotional or psychological development (Chen 245). Gehrman even notes that some critics claim Murfree’s ability to convey “emotional and moral states of human characters” was similar to that of Hawthorne’s (321). Alongside this, both readers and critics praised Murfree’s ability to depict such realistic forms of dialect that reflect the language of Southern Appalachia.

While, during her time, Murfree’s work was published, circulated, and enjoyed, it receives very little attention in the literary world today. Gerhman rightfully claims that both Murfree’s literary talent and intellectual abilities provide her work with a great deal of literary value that not only deserves much more scholarly attention than it receives, but that is rich with potential analyses of both the late antebellum south in America and of a woman’s—particularly a woman writer’s—place within it.

What Murfree Can Tell Us

What is particularly interesting about Murfree’s career as a woman writer in relation to her female protagonist in “The Mystery of Witch-Face Mountain” is the story’s underlying message about the experience of women in the nineteenth century. Despite her tenacity and dedication to the art of not just writing but producing notable works of literature, Murfree had but a short-lived career that proved virtually no legacy. And despite Narcissa’s passion for the town’s remarkable natural landscape—the only element in the story that essentially worked as a buffer between the southerners and those associated with the urban world of production outside of it—her thoughts were dismissed, and ultimately the community did not benefit.

Such a connection seems to reflect the importance of literary recovery and to illuminate what society potentially risks if we do not listen to the voices of those who have been systemically silenced. Not only will we miss out on great works of literature, but also what that literature seeks to tell us about both society and women’s place in it. As Murfree has demonstrated in her text and in her career as a writer, it would be a disservice to not only ourselves as individuals, but to both our literary and cultural communities to only reinforce our biases and thus fail to see the beauty that lies right in front of us.

Other Notable Works

- In the Tennessee Mountains (1884)

- The Prophet of the Great Smokey Mountains (1885)

- In the “Stranger People’s” Country (1891)

Full list of Murfree’s works available here

References

Chen, Chih-Ping. “Murfree, Mary Noailles (1850-1922).” Encyclopedia of American War Literature, edited by Phillip K. Jason and Mark A. Graves, Greenwood Press, 2001, pp. 243-244.

Gehrman, Jennifer A. “Mary Noailles Murfree (Charles Egbert Craddock) (1850-1922).” Nineteenth-Century American Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook, edited by Denise D. Knight and Emmanuel S. Nelson, Greenwood Press, 1997, pp. 318-323.

Murfree, Mary Noailles. The Mystery of Witch-Face Mountain and Other Stories. The Riverside Press, 1895. https://archive.org/details/mysteryofwitchfa00cradiala/page/n8

Pattee, Fred Lewis. A History of American Literature Since 1870. New York: Century, 1921.

Pryse, Marjorie. ‘Murfree, Mary’. The Oxford Companion to Women’s Writing in the United States, edited by Cathy N. Davidson, Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 591.

The Atlantic Monthly, vol. 76, The Riverside Press, 1895. (URL)