A small, female terrapin attempted to cross the Longport Causeway to find a nesting site. After an unsuccessful effort, she was delivered in a cardboard box to Stockton’s Animal Care Facility where John Rokita, the college’s resident wildlife expert, took her out to examine her injuries.

The soon-to-be-mom had deep cracks in her left, front carapace—too severe to survive. She managed to hold on long enough to lay one egg, and with a bit of help, her other eight eggs were saved.

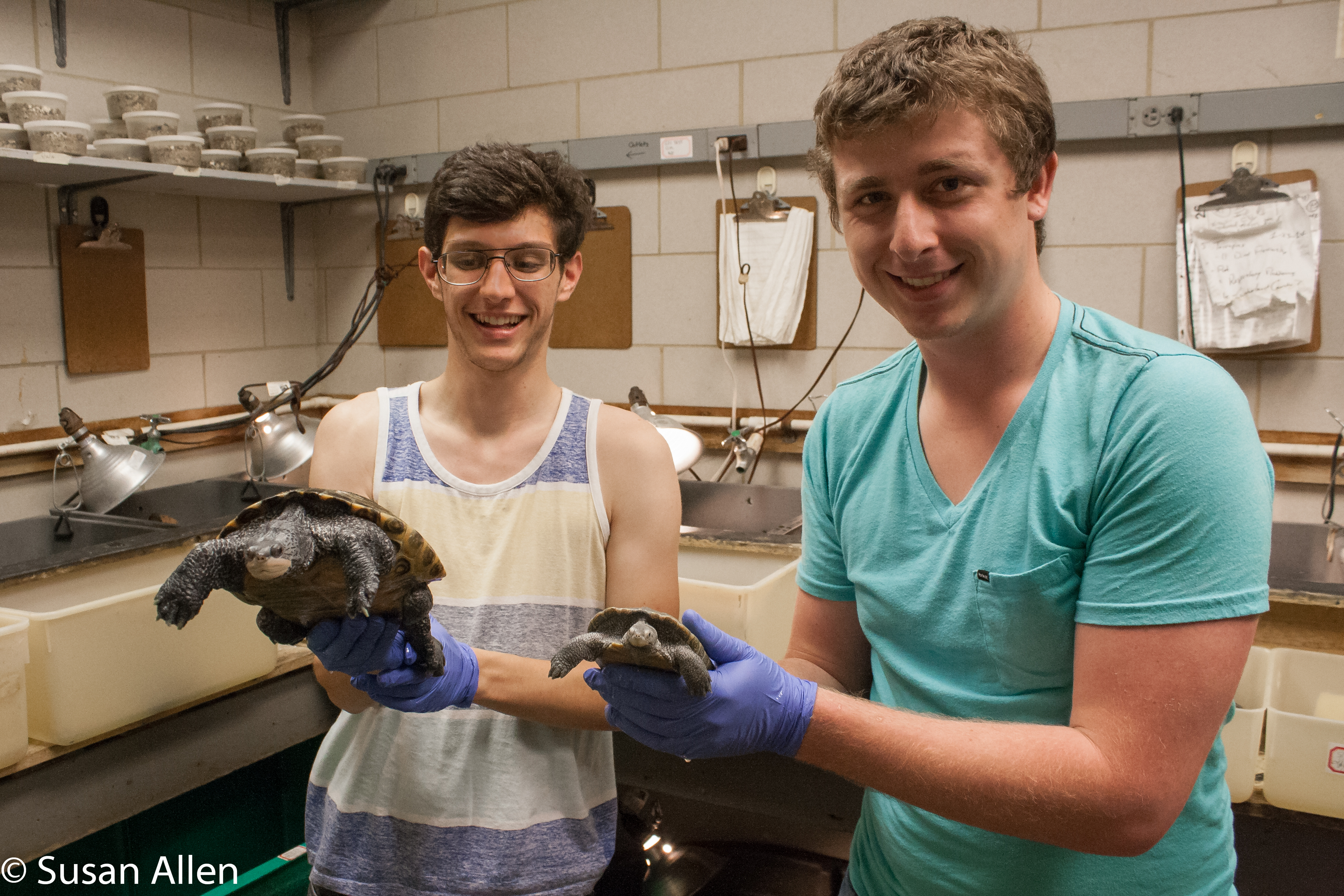

Rokita instructed Michael Carman, a sophomore Sustainability major, how to perform an egg-ectomy, a surgical procedure that was developed to extract eggs from road-killed terrapins.

After two months at 30 degrees Celsius in an incubator, the salvaged eggs will hatch out as female terrapins. There’ll be no brothers within the clutch because terrapins have a temperature dependent sex determination. Males only hatch when they are kept at 26 degrees and below.

Rokita explained that it’s important to return females back into the wild because they are at a greater risk. Gravid females cross roadways to lay their eggs on higher ground. The nesting season unfortunately falls between two major holiday weekends when shore traffic peeks. Males don’t often have a reason to cross highways as they do not go to the nesting sites.

After each egg was gently squeezed out of the oviduct, a few much smaller eggs remained. Rokita explained that a terrapin could lay multiple clutches in a season, so the smaller, undeveloped eggs would have been laid later this summer.

The nine reclaimed eggs, pinkish yellow in color, were rinsed and placed over vermiculite, a mulch-like material. Carman filled in the “egg map” on the underside of the container’s lid with information on where and when the eggs were collected. In a few days, after they begin to develop, the eggs will turn chalk white. The hatchlings will be released as close as possible to where they were found after staying the winter at the Animal Lab in optimal conditions for maximum growth.

The terrapin conservation project started in 1990 when Dr. Roger Wood, a former Zoology professor, attempted to hatch rescued eggs in his attic. After a summer heat spell spoiled his efforts, he looked to Stockton’s Animal Care Facility for a place to expand the initiative.

Rokita and the Animal Lab staff are humble and dedicated biologists, and they work hard to help a species that faces peril on the roadways by giving their offspring a second chance.

For more information on the terrapin conservation program, click here.