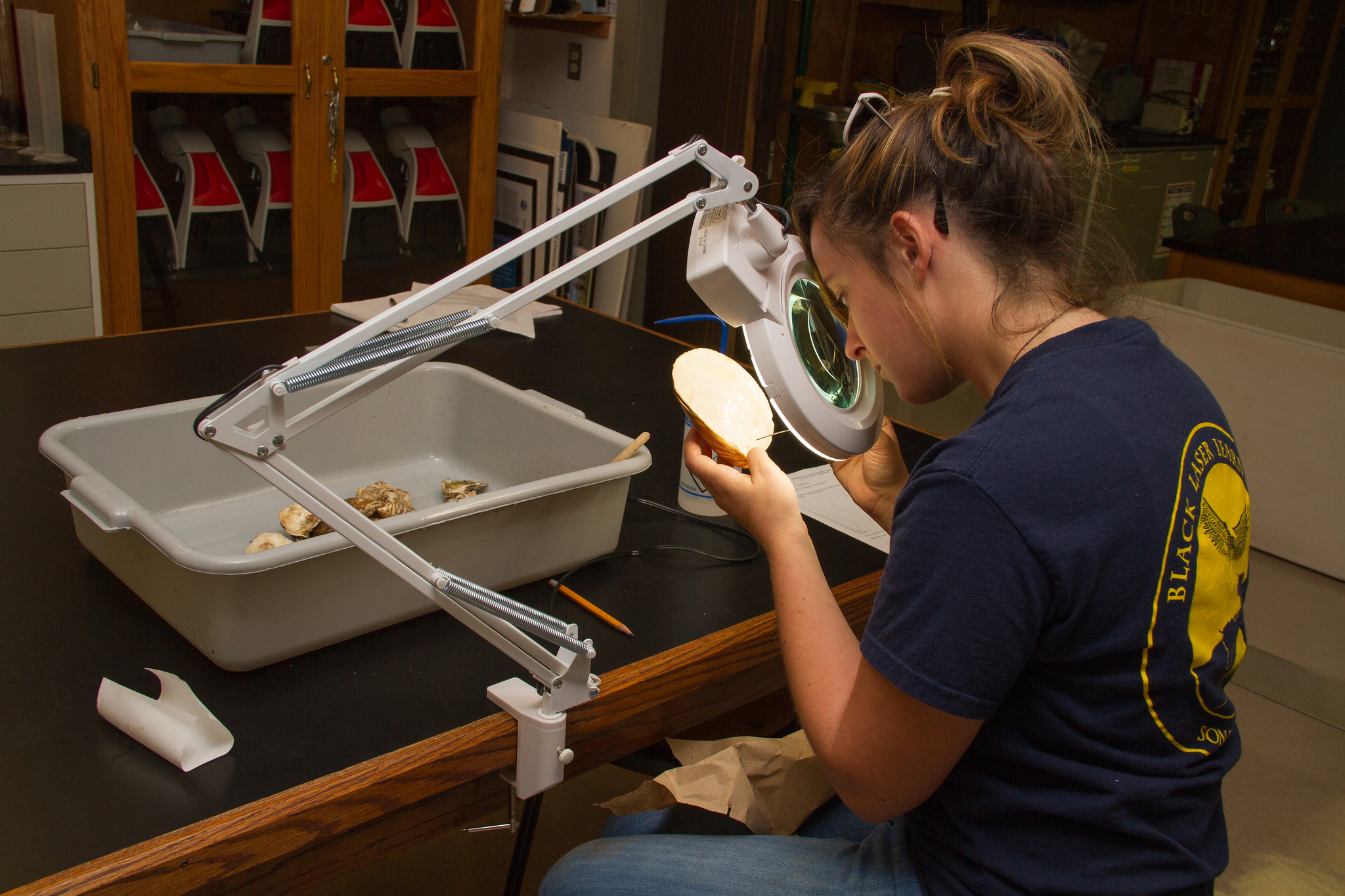

Emily Burnite peers through a jumbo magnifying glass—the kind one sees in a dentist’s office—to get a closer look at the brown splotches growing on the smooth, pearly-white interior of a surf clam. Burnite is looking at spat, the scientific name for young, developing oysters.

She carefully counts and logs the number of oyster larvae embedded onto the shell.

The Marine Science senior from Churchville, PA, worked with the Marine Science and Environmental Field Station this summer to get a clearer picture of the size and distribution of the oyster population in the Mullica River Great Bay Estuary.

She was awarded a Stacy Moore Hagan Memorial Scholarship in memory of the 1992 Stockton Marine Science graduate to participate in the field station’s oyster monitoring program as an intern. The scholarship internship program was established by Roland Hagan, a laboratory researcher at the Rutgers University Marine Field Station, who studied at Stockton and met his future wife Stacy at freshmen orientation.

Every other week, Burnite and a small group of student researchers go out into the bay with Steve Evert, manager of the college’s field station and assistant director of Academic Labs, to conduct field work. They are collecting spat at designated research sites to identify where oysters are thriving and where they aren’t.

Evert stops the boat at ten locations that “move across a salinity gradient” from the mouth of the river into the bay said Burnite. Water quality parameters such as pH, turbidity, salinity, dissolved-oxygen, temperature and depth are recorded at each site. Then an orange buoy is hoisted into the boat, and Burnite collects a mesh bag filled with 20 oyster shells.

When the bags are lifted out of the water, she hopes to find spat growing on the shells.

Currents transport miniscule oyster larvae through the water column, and eventually the baby oysters settle to the bottom where they adhere to other oyster shells and hard substrate explained Burnite. Some of the drifting oysters burrow onto the shells in the mesh bags, which are suspended one meter above the seafloor by a weighted buoy.

The shell bags are taken back to a field station laboratory where spat is counted. The number of spat at each of the ten sites is an indicator of how the oyster population is doing in each of those habitats.

Knowing where and understanding why oysters thrive in certain conditions can help scientists determine where to spread crushed shell on the seafloor to help create artificial reef for developing oysters. New oyster habitat can provide opportunities for recreational and commercial oyster harvesting.

“Oyster fishermen have built artificial reef from shells to help the population. We are trying to identify restoration sites,” Burnite said. “The goal is to establish a long-term oyster monitoring system of the area to aid in future restoration projects.”

Of her scholarship, she says that it has helped her “get as much experience as possible.”

The Stacy Moore Hagan Memorial Internship Program also gave her the chance to drive a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) through local shipwrecks and to use side scan sonar technology this summer.

Prior to getting involved with the oyster project, Burnite gained marine research experience through a number of internships, independent studies, coursework and volunteerism.

She has interned at the Rutgers University Marine Field Station, where she identified larval fish specimens collected with a bridge net, and at the Cape May Whale Watch and Research Center where she used photography and image analysis to help catalog the local population of common bottlenose dolphins. At Stockton’s field station she has calculated seagrass biomass to determine restoration potential.

Through an internship with Dr. Mark Sullivan, associate professor of Marine Science, she worked with Stockton’s field station and NOAA’s Marine Debris Program to retrieve abandoned crab pots that continue to trap marine life on the seafloor using sonar technology.

While taking an Underwater Robotics course, she mentored 4th and 6th graders who built an underwater submersible with the SeaPerch program. “Getting to see kids that young interested in science and technology was awesome,” she said.

Burnite is a member of Stockton’s Marine Science Club and the Washington D.C.-based Marine Technology Society. She is also a certified open water diver.

She is grateful to be working closely with faculty and staff on research projects that impact the region and to be using state-of-the-art technology. When she graduates this year, she’ll not only have a degree, but she’ll have a skill set and experience with marine technology that most students don’t gain until graduate school.

“Coming to Stockton was my best decision,” she said.

“I would never ever have thought of myself as a distinctive student, or…thought I would have come as far as I have. I owe it all to Mark [Sullivan], for seeing something in me I did not, to Tara [Luke, associate professor of Biology], for opening my eyes to marine technologies, and to Steve [Evert], for being an amazing mentor. All have encouraged me to keep working as hard as I have to become the marine scientist I am today. I did not even believe I was smart enough to pursue anything in the biology field back in high school. My teacher, Jeffery Warmkessel was the one who I owe everything to because he told me I could do it when everyone else said I could not. Now, I have this internship and I’m graduating soon as a Marine Science major with a 3.8 GPA,” she said.