But Still Holding It Together: Our Oldest Texts

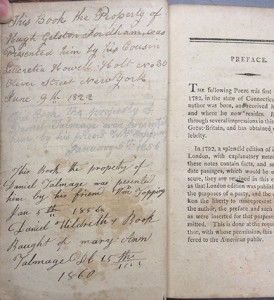

Why care about the oldest texts Stockton holds in the depths of Special Collections? Why? Because there is something about holding a book, a book that might have been held by a president, a scholar long dead, or a common man or woman whom you’ll never meet. Old books connect us to previous readers and to our past. Read an old book and your path crosses that of another. And each book, if read properly, has a story to tell.

Special Collections, located on the ground floor of Stockton’s library, preserves these texts in ways in that technology cannot. Digital copies may duplicate the information that a book holds, but they cannot preserve the book itself. Special Collections not only preserves the physical object, but provides appropriate access to these rare, old texts. They serve as a promise to future generations: they too will be able to study these artifacts from our past. They too will be able to develop connections with books that are hundreds of years old—the kind of connections you can only have with an old book.

*

The Printing Press and Stereotype

Today, we type up a document in Word and just click “Print.” Miraculously, the words appear on the page in seconds. This process used to take longer—much longer. Moveable type was arranged by hand, letter by letter, in reverse order. Once a page of text was set, it could be printed onto paper. The same page was printed over and over until the correct number of copies was created. Then the type was broken down and the next page was set. This was very time consuming. If more copies were needed of the same book (for example, the Bible was constantly reprinted), the process was repeated for each reprint.

In 1725, a Scotsman named William Ged invented a new way of printing which allowed typesetters to streamline their process—stereotyping. According to The Encyclopaedia Britannica, this is, “a process in which a whole page of type is cast in a single mold so that a printing plate can be made from it.” This process cost the printers more time initially, but if a book had to be reprinted later, the printing plates would save them a great deal of time and money. Initially, printers did not accept Ged’s work, and it went mostly unused until the early 1800s when Charles Stanhope revived the process. Ged managed to get a contract with Cambridge University to print Bibles in this way, but eventually he abandoned the project and returned to his trade as a goldsmith.

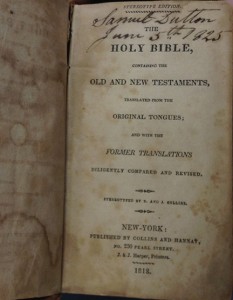

In the United States David Bruce first made stereotype plates of the Bible in 1814. This copy of The Holy Bible was printed using stereotype in the year 1818. This made it more affordable and easier to mass-produce. Surprisingly, according to WorldCat, there are only twelve other copies of this book in libraries around the world.

*

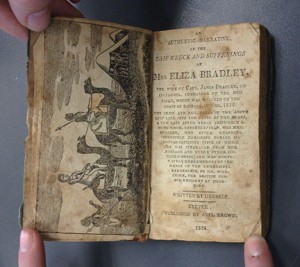

Small Books with a Large Purpose

In the 1800s, it was no rarity to come across a small book filled with information. We see analogous miniaturization today, but no longer in book form; now we access information through our cell phones. With countless apps, eBooks, and the internet in the palm of our hand, it is unnecessary to carry books on a daily basis. Nevertheless, accessibility and convenience were not ideas invented by the digital age. Enter the book in small format. Bibles, psalm books, and pleasure texts were all available in pocket sizes for readers to carry with them as they pleased, much like the multipurpose smart phones we carry today. Because many churches in the 1800s did not supply bibles and psalm books, parishioners arrived with books in their pockets ready for worship. Compare this to the eBooks available on iPhones and Androids. Whenever we have a spare moment, we’re on our phones reading or occupying ourselves wherever we please; no small books necessary.

*

New Jersey Laws

The Laws of The State of New Jersey was compiled by William S. Pennington and printed and published by Joseph Justice in Trenton in 1821. The work is broken into chapters consisting of “The Constitution of New Jersey,” “The Declaration of Independence,” “Constitution of The United States,” and “The Amendments.” The book describes in great detail each New Jersey law, and is complete with Appendix, References, and Index. Some of the early laws detail the arrangements made with Native Americans. Others settle boundaries between Somerset, Middlesex, and Mon-mouth counties. Another act details the preservation of the rivers and forests of New Jersey. Relief for the poor was established by law in 1774. The regulation of wagons within the state is also described in addition to an act for the preservation of cranberries. On November 24, 1794, an act was passed preventing the burning of woods, marshes, and meadows. One of the most interesting acts concerned marriages. It states that no man shall marry his grandmother, grandfather’s wife, father’s sister, mother’s sister, son’s wife, sister, son’s daughter, daughter’s daughter, son’s son’s wife, mother, step mother’s daughter, wife’s daughter, brother’s daughter or sister’s daughter. This 900-page work reveals innumerable details about New Jersey’s rich cultural past. In 1821, its purchase price was $20.

*

Complete Latin Lexicon of 1771

This large folio volume was printed in Padua in 1771. Stockton currently owns three volumes of the Lexicon: two from 1771 and one from 1831. Remarkably, the two older volumes are in better condition than the newer. However, all three are in fragile condition and must be handled with care. The Lexicon represents the life work of Egidio Forcellini (1688 – 1768), Italian philologist, who studied under Jacob Facciolati at Padua. Unfortunately, he died in 1768 before completing this great work—a lexicon or dictionary of the entire Latin language—on which he had co-operated with Facciolati. This work laid the groundwork for countless Latin lexicons to follow.

Forcellini, Egidio, and Jacob Facciolati. Totius Latinitatis Lexicon. Padua: by Joannem Manfrè, 1771.

*

Fashions for the Masses

Think of the phrase “Don’t judge a book by its cover.” Books not only tell stories through the words printed on their pages but also through the condition of their covers, bindings and the material inside. These stories tell tales of longevity and ownership, significance and usage. In this era, we have become less reliant on physical books and more dependent on technology. Yet as times change we should cherish the old texts that remain and preserve them for future generations. Preservation is the key to the life expectancy of a book just as health is to humans.

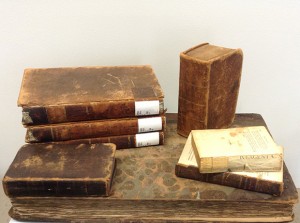

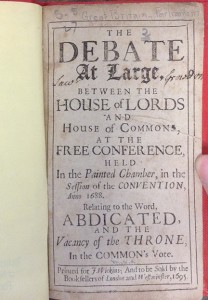

Tucked away inside the secure, climate controlled walls of Special Collections lies a family of books: Travels through the Northern Parts of the United States in the Years 1807 and 1808, volumes I-III. This family, over 200 years old, sits quietly, waiting to be utilized. Their original bindings are still intact, and though their pages have decayed somewhat, they are still in useable condition. This may suggest that these texts have been handled with care or perhaps have not been thoroughly read. The Debate at Large (1695), another book in Special Collections, has been rebound, most likely because of heavy use and its significance. Still meaningful at 319 years of age, The Debate at Large was rebound to lengthen its lifespan, leaving the text in even better condition than Travels through the Northern Parts of the United States in the Years 1807 and 1808, volumes I-III, though it is 114 years older. The Debate at Large, having been repaired, will most likely outlive the Travel texts due to its preservation.

Kendall, Edward Augustus, ESQ. Travels Through The Northern Parts of the United States in the Years 1808 and 1809. New York: I. Riley, 1809.

The Debate at Large, between the House of Lords and in the House of Commons, at the Free Conference, Held in the Painted Chamber, in the Session of the Convention, Anno 1688 Relating to the Word, Abdicated and the Vacancy of the Throne in the Common’s Vote. London: Printed for J. Wickins, and to Be Sold by the Booksellers of London and Westminster, 1695.

*

What’s the Forecast?

The precursor to Modern Meteorology

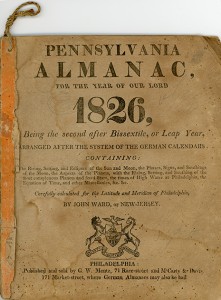

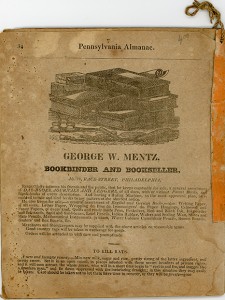

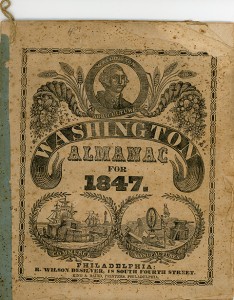

Prior to modern meteorology, almanacs were a staple in households around the world. They predicted weather patterns a year in advance, suggested when farmers might plant crops safely, and helped their readers keep track of the days and months of the year. According to The Oxford English Dictionary, an almanac is, “An annual table, or (more usually) a book of tables, containing a calendar of months and days, with astronomical data and calculations, ecclesiastical and other anniversaries, and other information, including astrological and meteorological forecasts.” Almanacs have been used for hundreds of years—they have been around since before modern English even existed and are still used to this day. Here are two almanacs held in Special Collections, but there are hundreds that have been published in America alone. The University of Minnesota has a collection of over 250 almanacs published in English and an additional 50 in other languages.

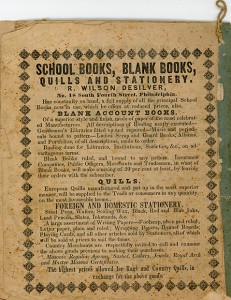

Both of these almanacs were published in Philadelphia, but they served the South Jersey region as well. They are in great condition, which is remark-able considering that they are made of plain paper and that they are over 150 years old. All of the pages are intact, and each one still has its original string in the upper left-hand corner. Users would have installed the string themselves so that the almanac could be hung on a hook for easy access. The almanac would have been referenced often within the household.

*