The Israel and William Chew Account Books

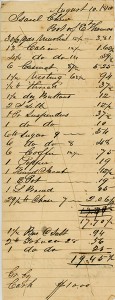

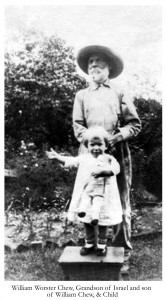

According to genealogical records, Israel Chew was a farmer and tavern keeper, although his account books make clear that he was also a grocer. His son, William, was a blacksmith. Israel, son of Contine Chew, was born in 1792 and lived throughout his life in Burlington and Camden Counties, specifically in Evesham and Waterford Townships. Israel married Hannah Worster in 1817 and the couple had nine children. Israel died in 1874 and Hannah, who was born in 1799, died in 1886. William Henry Chew, their third son, was born in 1824. William was a blacksmith and a Civil War veteran, residing at different times in Waterford and Shamong Townships. He married Elizabeth ca. 1848, and they had seven children; he died in 1917. One of his sons, William Worster Chew, is pictured in the accompanying photograph. Israel and William are buried at the Chew family cemetery near Waterford, NJ.

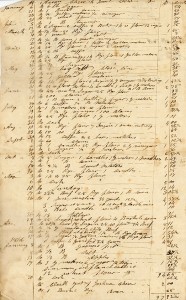

Family members preserved the 12 Chew account books held in Special Collections, dating from 1830 to 1869, until donated to Stockton’s Library. The Chews’ lineage has been traced from its origins in England through their movement to Virginia, then to Philadelphia, and finally to South Jersey. Although the account books may seem sharply focused, recording the financial transactions of Israel, tavern keeper and grocer, and William, blacksmith, in fact they provide a clear and intriguing window into the daily life of mid-nineteenth-century South Jersey.

*

Notes to Chew

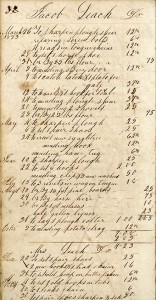

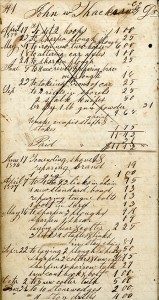

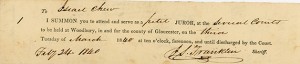

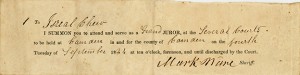

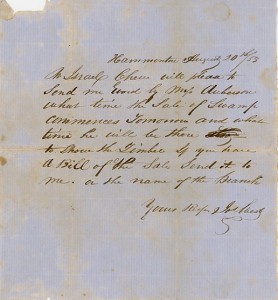

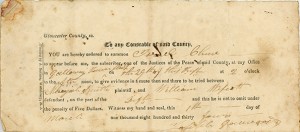

Israel and William Chew’s account books are more than just straightforward economic records. A quick glance reveals the style and manner of these 19th-century blank books, which are beautifully written by hand in ink, precisely separated with lines, and organized by date. The whimsical calligraphy is one of the most appealing aspects of this collection, an aspect of writing that technology has almost wholly eradicated today. Tucked between the pages of these account books, which date from the 1830 to the 1869, are numerous paper notes to the Chews, everything from to-do lists and shopping lists to jury summons. Today, even the simplest notes are digitized as text messages or emails. But there is something about a handwritten note that is more personal and social. It is as unique as a voice or a fingerprint. Handwriting is aesthetically pleasing; it makes even a simple note more appealing than the standardized letters that are automatically structured onto the page as I type this blurb. Will handwriting become obsolete? Will these little handwritten notes, like the ones to Israel and William Chew, become a showcase of the past?

*

Pieces of the Past

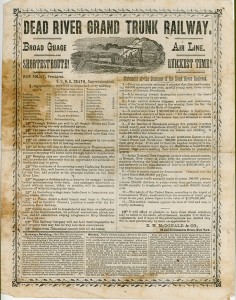

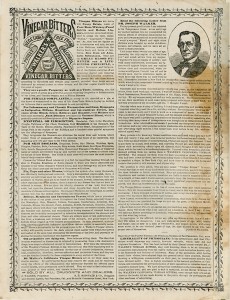

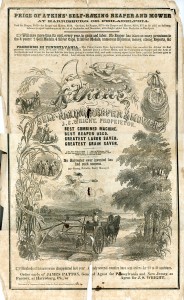

Is it possible to learn about culture within an account book? It is in the Chew Collection held in Stockton’s Special Collections. Jury duty notices, bills, notes, and newspapers found neatly tucked between the pages of these 19th-century account books offer a glimpse into South Jersey life more than 150 years ago. Israel and William Chew, father and son, may not have intended their loose papers to be recovered or read by 21st-century students of South Jersey. Perhaps while casually reading the newspaper, a customer or errand called on Israel or William’s attention, causing him to fold and tuck it between the pages of his account book. Perhaps he was saving the article for a friend to read later in the day. Perhaps, this was the Chews’ haphazard filing system. Whatever the reason, this happenstance has preserved a trove of intriguing documents.

One of the account books contains a promotional newspaper headlined by a temperance essay entitled “Dead River Grand Trunk Railway.” Inside are shorter articles with titles such as “Parental Government” and “Woman’s Virtue.” These articles present a slice of history, voicing particular social attitudes that are far from today’s norms. The language of the articles is interesting, serving as it does to propagate and reinforce social attitudes and expectations with clear emphases on the acceptable roles for men and women. Ideals of subjugation and oppression of women are prominent and disturbing. These attitudes were not only indicative of 19th-century American culture but quite clearly circulated throughout South Jersey too.

*

Cucumber Man

Browsing through the accounts in the Chew Collection, one can find many interesting purchases such as tobacco, buckwheat, horseshoes, and nails. The most interesting purchases (at least among those which are legible to 21st-century readers) may be those of Anthony Discon in 1850. Almost every time Discon went to Israel Chew’s grocery, he bought himself a cucumber and a gallon of molasses, and once, a bar of soap. Apparently, Discon liked his molasses, and he seems to have been the only person to purchase cucumbers. Most of the time, he would only buy one, maybe for a snack on the ride home. Interestingly enough, he once bought over 20 cucumbers in one visit to Chew; perhaps he dipped them in his molasses that night. No one will ever know.

Some of Chew’s customers worked to off-set outstanding store balances by doing odd jobs. In 1847 Jacob Simons, who was often paid for completing small tasks, was given the unfortunate task of hauling dung. Hopefully, he was paid more for this work than his other jobs, which included plowing and shaving shingles.

*

Loose Papers of the Chew Collection

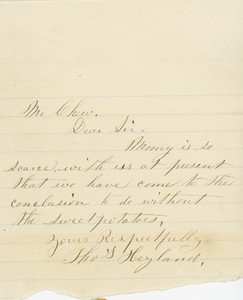

Every time a Chew account book is opened, something new can be found between its pages. Whether a small detail on a page, or another loose paper, those things bring us closer to the families and the people who purchased goods and services from the Chews. Many of these curious scribblings are legible if studied for long enough. Seemingly unreadable passages give up their meanings as readers piece together clues and eventually recognize words, phrases, and entire sentences.

These odd scraps include personal notes, bills, even lists of numbers. Maybe more curious than the others, is one of the smaller papers found within the pages of William Chew’s Longacoming 1850 account book, between a small envelope and a jury summons. Written on now faded lined paper, this tiny note discusses, simply, sweet potatoes. The author, Mr. Heyland, politely explains that funds are too tight to squeeze the sweet potatoes into his order. There is poignancy to notes such as this.