“We read of all-round women… And yet, with all this infinite variety, the all-round nature holds all in such true balance and poise, develops in such fine proportion, as never to seem to be all sympathy or in all sense, or anything but a rounded and symmetrical whole,”

Mary Lowe Dickinson (1912)

Born Mary Caroline Underwood on January 23, 1839, in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Mary Lowe Dickinson was a 19th- century American writer and activist.

Beginning her career at the age of 15, Dickinson became a schoolteacher and displayed great talent as an educator. During the period of her teaching, she would also marry her first husband George P. Lowe in 1858, to whom she dedicated herself emotionally. His early death, in 1863, had cast a “great shadow upon her early life,” (Emerson 101). Following his death, Dickinson evaluated herself and realized two things: 1) she had a natural born passion for education, and 2) the drive she possessed should not be taken for granted. She would continue to work in education and would ultimately take on the role of assistant principal of the Hartford Female Seminary (Underwood 61).

At the age of 24, she was set to become the vice-principal of Vassar College upon its opening in 1861—however, an opportunity to study abroad and travel in Europe presented itself and she followed that route instead. For the next few years, Dickinson served as a tutor for two separate families and wrote for several journals “contribut[ing] at one time regularly to no less than thirteen periodicals,” (Emerson 102). Upon her return in autumn of 1867, Dickinson would return to work as administrator in education and become principal of one of the most important boarding schools in New York City: Van Norman Institute (Emerson 102). During her first year as principal, she would meet and marry her second husband John B. Dickinson and ultimately leave the position for other ventures.

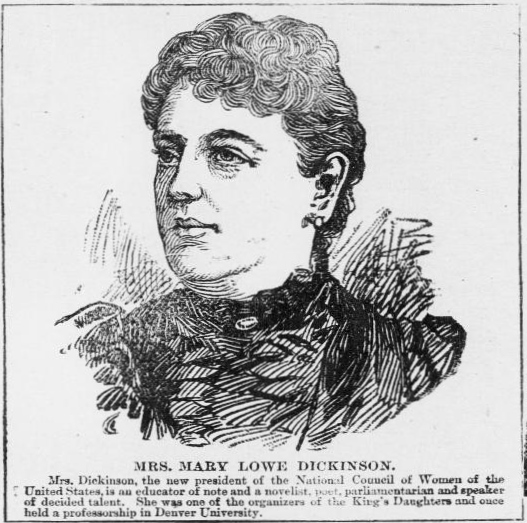

Being with her second husband allotted her the ability to provide to the public monetarily seeing as she had external funding available to her. However, when he died in 1875, that financial support was removed, and she had to return to work. Seeing as she could no longer give money, she had turned to giving what she bountifully had left: herself. During their marriage, while Dickinson was seizing the philanthropic opportunity, she had established herself as a remarkable social worker, writer, and lecturer on philanthropic and social questions (Underwood 62). This opened the door for her to become an active member in several of the most prominent reformatory organizations of her time. Her most notable membership statuses include superintendent of the department of higher education in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, general secretary of the International Order of the King’s Daughters and Sons (a position she held until her death), and her election as president of the National Council of Women of the United States in 1895 (National Women of the United States 217). The work she provided while active in these organizations, and many others, had a strong influence on her writing as she branched out into poetry and fiction writing.

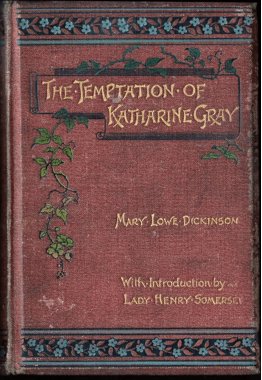

Dickinson is quoted as having written “for the cause which interested her,” (Logan 715). Her work was recognized as having “the power of making the individuals [reading] live out the tale before [their] eyes,” (Logan 715). She wrote several novels that were praised as such, one of which is the primary focus of this recovery: her last novel, The Temptation of Katharine Gray (1895), which had been considered “the strongest analytical work and the best character-study that has yet appeared from her pen,” (Logan 715).

The Temptation of Katharine Gray by Mary Lowe Dickinson

“To dare all things and defy all things for the love of a child… one comes to choose wrong-doing for one’s own sake… [and] is a form of woman’s development that few […] would ever care to trace, however dramatically presented”

The Temptation of Katharine Gray by Mary Lowe Dickinson, page 6

Dickinson’s 1895 novel, The Temptation of Katharine Gray, tells the story of a mother willing to “live and suffer and toil and endure for the sake of [her] beloved child,” (Dickinson 6). According to Dickinson, what makes a remarkable novel is an author’s ability to create a narrative that the readers can apply to their own lives, allowing them to adequately follow the characters’ journeys.

Her novel begins without hesitation to introduce the main conflict: Katharine Gray’s destructive marriage to her husband Robert Gray. Katharine works as a laundress to provide for herself, their child Gretta, and her husband. Robert, having come from a wealthy family, is revealed to have no sense of work ethic, which shines through as the reader learns he regularly infringes upon the family’s financial security through his gambling addiction and alcoholism.

One night, when Katharine and Robert get into an argument over how his addictions impact Katharine’s abilities to take care of their infant child, he storms out leaving Katharine shaken and fearful. In her worry, Katharine writes a letter to her older sister in Boston, telling her about how she fears for their safety and feels she must leave. Robert comes home before she can get it hidden or perhaps even sent, and she hides it. The next day, while she is out at work, Robert rummages through Katharine’s things, looking for money she might be hiding from him, and finds it. He becomes irritated and takes the letter to his parents, insisting that Katharine plans to desert both Robert and Gretta, and that their child must be placed into their care. In doing so, Robert hides his ulterior motive; seeing as Katharine will no longer support his habits, he believes that by placing Gretta into the hands of his parents, they will also continue to provide for him financially as they had prior to his marriage. He is able to convince his mother and one day, when Katharine leaves the house to pick up her earnings from her job, Robert leaves with Gretta and fulfills his plans.

Katharine returns to an empty house and begins to panic. She turns to her upstairs neighbors, the Burkes, for support. From there, the story begins to follow the development of Katharine’s relationships to Biddy and Biddy’s son Theodore, who takes a particular interest in Katharine. Blind to the attachment he is developing for her, Katharine asks Theodore to help her find Gretta. She explains to him that she must go to Boston to visit her sister since she is sick, which she learns in a letter that she received in the midst of all the already developed chaos, and Theodore willingly accepts his mission. Katharine leaves for Boston the next day and Theodore immediately gets to work.

While on her trip, her sister dies from her illness and asks Katharine to take care of her infant child, Margaret, and Katharine promises her she will. Soon after, Katharine returns home with the child, to find out Theodore had found Gretta. Katharine takes immediate action after learning her whereabouts and steals her child back. Robert learns of this and employs police officers to find his wife and his child, to jail Katharine and place Gretta back in his possession. However, before he can, Katharine establishes a plan with Theodore: she will take the train with Gretta to flee to Chicago. To avoid suspicion and reduce the chances of them being caught, he shall take the same train the next day to bring Margaret to her. Unfortunately, Theodore is caught and the child, who they assume to be Gretta, is taken and placed in Robert’s custody. Katharine, already filled with unease about having selfishly separated the group to improve the chances of her keeping her child, is made aware of what happened as the train arrives at Michigan Central (the train’s first stop) and she over hears other passengers talking about it.

Katharine must now decide what she will do for the safety and security of her child. She finds herself in the hands of the Shaker Community of Loriston, who have connections to her sister’s husband’s family, the Maitlands. Reconnected with Marion Maitland, the two decide that it would be best for Katharine to have some separation from Gretta so she can gain a proper education and Katharine can spend some time figuring out herself and gathering her own life. The issue that lies here, is that Mrs. Maitland is under the impression that Gretta is not Katharine’s biological daughter, but instead that the child she has is her sister’s. Katharine decides that this confusion is her best opportunity to have both children she is responsible for to be raised in prosperity, seeing as Margaret is in the care of the Grays who can provide for her to no end. So, Katharine takes on the guise of Gretta’s “aunt” and lets her get sent away to school. However, this ruse begins to lose its luster as Katharine becomes reconnected to the Burke family.

Katharine’s past begins to resurface itself as Theodore begins to develop a closer relationship with Gretta, now that she is a teenager. Theodore also begins to question Kathrine’s morals, as she has let this family provide for her and her child, under the impression that they have been providing for their own this entire time. During this, Katharine also learns that Robert has fallen sick and has been under Margaret’s care. Driven by her guilt, Katharine leaves to go relive Margaret of her care giving duties as a means to quell the inner turmoil she is facing as result of her “sin”.

The story concludes with the truth revealed, as it was bound to. Margaret returns with Katharine to the Maitland’s estate where she is introduced to her family. Mrs. Maitland learns all of what had gone on and Katharine’s explanation from it all. Reasonably upset she had been deceived, Mrs. Maitland is also overjoyed to finally be able to provide for and develop a relationship with her true niece. Time passes, and eventually Margaret marries a close family friend of the Maitlands, Theodore and Gretta marry as well, and the mother-daughter pairing redevelop a more healthy relationship. Katharine is given the space to grow into her own person, without the crushing weight of fear and motherhood, and decides to try her hand at becoming a writer.

Dickinson’s Cultural Significance

During her lifetime, Mary Lowe Dickinson had become a prominent name among women activists and authors. She managed to spread her progressive hopes for women’s rights through her poetry and fiction writing (such as The Temptation of Katharine Gray which addresses areas discussed within divorce reform and the temperance movement, both Dickinson was part of).

In 1886, the International Order of the King’s Daughters and Sons was established. Dickinson listed as one of the original nine members in attendance on the night of their first meeting (IOKDS, Web). As previously mentioned, one year later she would take the position of general secretary. As part of the International Order of the King’s Daughters and Sons, Dickinson contributed to the efforts of providing “service to others” and doing “any work that involved doing good In His Name,” (IOKDS, Web). The work message she was spreading as part of the IODKS, operated in conjunction with her status as a member of the National Council of Women of the United States. During her election as president in 1895, the NCW had expressed support for issues such as divorce and dress reform, and “equal pay for equal work,” (The Herald, Web). She would also assume the position of the national superintendent of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union’s higher education department (Underwood 104).

Dickinson was not the only notable name listed among the member rosters of the organizations listed above; she was also in regularly in the company of Elizabeth Lady Scranton and Susan B. Anthony. Stanton and Anthony would establish the National Woman Suffrage Association, which expanded, leading to the establishment of the International Council of Women, which operated in affiliation with the NWC. While there is no confirmation on what their relationships were, by knowing who Dickinson was associated with, it helps to bring clarity to the mindset she was writing in, especially when comparing it to the political and cultural climate she was living in.

Her philanthropic nature was not with flaw, though. Additionally, she was elected as president of the Women’s National Indian Association in 1885 (Mathes 25). This organization’s main goal was the assimilation of Indigenous people, converting them to an Anglo-Saxon way of life, and was ultimately dissolved in 1951.

Why study Dickinson?

Mary Lowe Dickinson can be considered a woman of mysterious excellence. She was a writer, an educator, and an activist. But more than all of this, she was modest and reluctant to revel in her accomplishments, despite being an incredibly accomplished woman. Dickinson herself did not believe in her own talents and is quoted as repeatedly saying “Talent uses us… If I had a spark of it, I could not have waited for circumstances to force me to use it,” (Emerson 102). This attitude is a testament to how the reluctance of women in taking unapologetic pride permeates through the sands of time. It was not as if Dickinson did not have peers who fought against this—Elizabeth Cady Stanton was known for making waves and was even outcast from her organizations for doing so—but, that wasn’t Dickinson’s style. With this considered, it emphasizes the need for attention for 19th century women authors. Clearly, they could be read about in newspapers, seeing as several are cited in this account, but we should not let them remain only there. We should read and piece together and develop their stories, so we can cohesively further our knowledge of 19th century women’s rights activists, like Dickinson.

Other notable works

Access to these works can be found by clicking the title.

Poetry

- Home from the War: A Rhyme for Thanksgiving by Mary Lowe Dickinson (1898)

- In the Afterglow: Poems by Mary Lowe Dickinson (1905)

Prose

- Among the Thorns: A Novel by Mary Lowe Dickinson (1880)

- The Temptation of Katharine Gray by Mary Lowe Dickinson (1895)

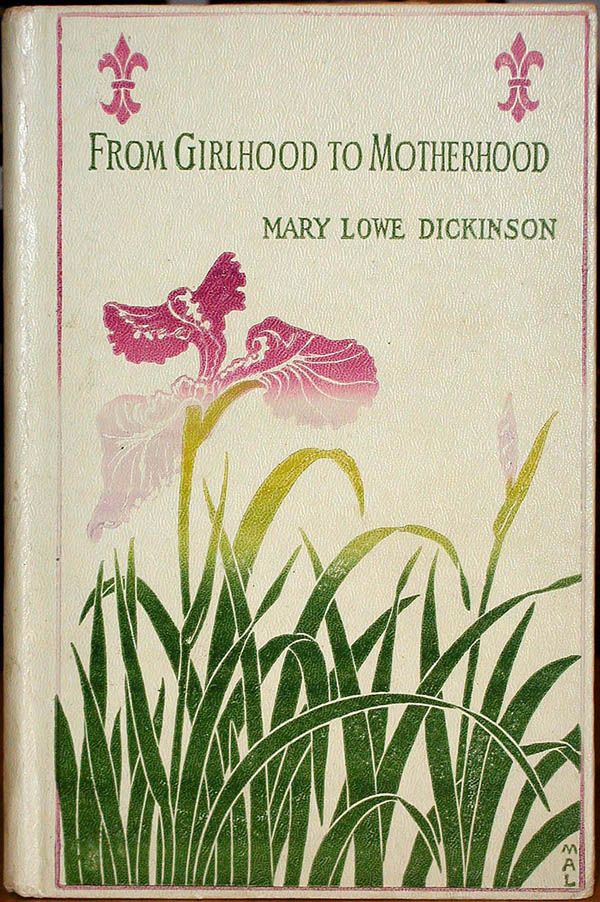

- From Girlhood to Motherhood by Mary Lowe Dickinson (1899)

References

Dickinson, Mary Lowe. The Temptation of Katharine Gray. United Kingdom, A. J. Rowland, 1895.

Emerson, William Andrew. Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Past and Present. Fitchburg, Press of Blanchard & Brown, 1887. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/01011384/.

Logan, John A., Mrs. The part taken by women in American history. Wilmington, Del., The Perry-Nalle publishing co, 1912. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/12002975/>.

The Women’s National Indian Association : A History, edited by Valerie Sherer Mathes, University of New Mexico Press, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/stocktonnj-ebooks/detail.action?docID=1865282.

The Herald. [microfilm reel] (Los Angeles [Calif.]), 27 Feb. 1895. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042461/1895-02-27/ed-1/seq-1/.

Underwood, Lucien Marcus, and Howard James Banker. The Underwood Families of America. Vol. 1, Press of The New Era Printing Company, 1913, https://archive.org/details/underwoodfamilie01unde/page/120/mode/2up.