Biography

Mary Dummett Nauman Robinson was born on April 13, 1839 at Hancock Barracks, Houlton, Maine to Lieutenant-Colonel George Nauman and Mary Henry Douglas Dummett (Leonard 696). The oldest child of the couple, she lived in St. Augustine, Florida with her mother and younger siblings while her father was stationed at various military posts (Meginness 91). Her maternal grandfather owned one of the first sugar cane plantations in Florida (Meginness 91). The Nauman family relocated to Lancaster, Pennsylvania during the Civil War after her father refused a high-ranking officer position in the “unholy cause” of the Confederate military and quickly applied for service in the Union, “never forgetting for one moment his devotion to that Constitution which, while yet a boy, upon entering the Military Academy [West Point], he had sworn to support, and that Flag under which he had so often fought” (“LTC George Nauman”).

Mary D. Nauman was educated in Charleston, South Carolina (Leonard 696). Between the late 1860s and the mid-to-late 1870s, Nauman published several children’s books as well as various poems, multiple short stories, and a serial titled Colonel Robinson’s Boys in periodicals such as Peterson’s Magazine and Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine. Her notable children’s books include Sydney Elliott (1869), Twisted Threads (1870), Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land (1872), The Enchanted Princess (1872), and Clyde Wardleigh’s Promise (1873). In 1875, at age 36, she married Captain Frederick Robinson, who was born in Lisnaskea, Fermanagh, Ireland on March 28, 1832 and died about seven years after their marriage on November 2, 1882 (“Frederick Robinson”).

Later in her life, she became the manager of the Ann C. Witmer Home for Widows (Leonard 696). She was against women’s suffrage (Leonard 696). Additionally, she was a member of the executive committee of the Lancaster County Historical Society (Bausman 147). Mary Nauman Robinson contributed a great deal of papers on local history, most concerned with genealogical research, including a 1911 essay that documents the details of slavery in Lancaster omitted from conversation around the subject by her contemporaries. In “Sidelights on Slavery,” she notes that “Lancaster county appears to have been a Mecca for those who, prompted by that love of liberty which seems to be inborn in the human breast, sought freedom from the toils and shackles of slavery” (Robinson 140). At 81 years of age, Nauman passed away on November 18, 1920 (“Mary D. Nauman Robinson”). In her obituary, she was remembered for her active role in the community, her literary attainments, and her devotion to Lancaster County history (Bausman 147).

Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land (1872)

“And then Eva did just exactly what either you or I would have done if we heard a great green toad talking to us. She went slowly through the tall grass down to the very edge of the pond.”

page 12

Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land is an 1872 children’s book by Mary D. Nauman. J. P. Lippincott & Co. published the text again in 1874 in a single volume with Clara F. Guernsey’s The Merman and the Figure-Head as part of the Enchanted Fairy Library series.

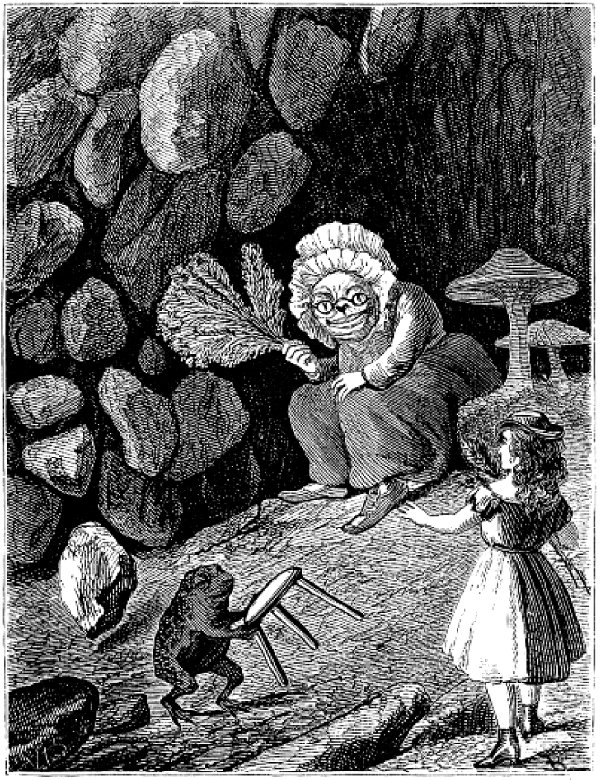

The story begins with a young girl named Eva, who is described as a fair little girl with blond curls, blue eyes, and an impeccably gentle nature. After spending all day long reading fairy tales, Eva decides to make a fairy tale for herself to occupy her imagination. For Eva, making a fairy tale for herself entails sitting in a grassy field, collecting flowers, and quietly observing the insects that surround her. She is just starting to doze off when she is startled by the noisy croaks of a toad. Curiously, Eva follows the toad’s instructions for her to follow it to the pond. As she stares into the pond, she sees a full moon with a face that winks at her and at times resembles the toad. Here, she suddenly falls unconscious.

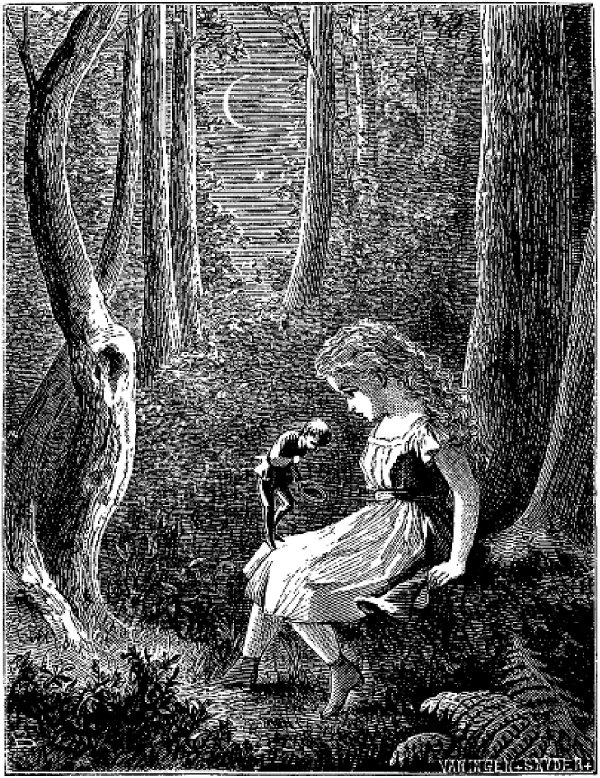

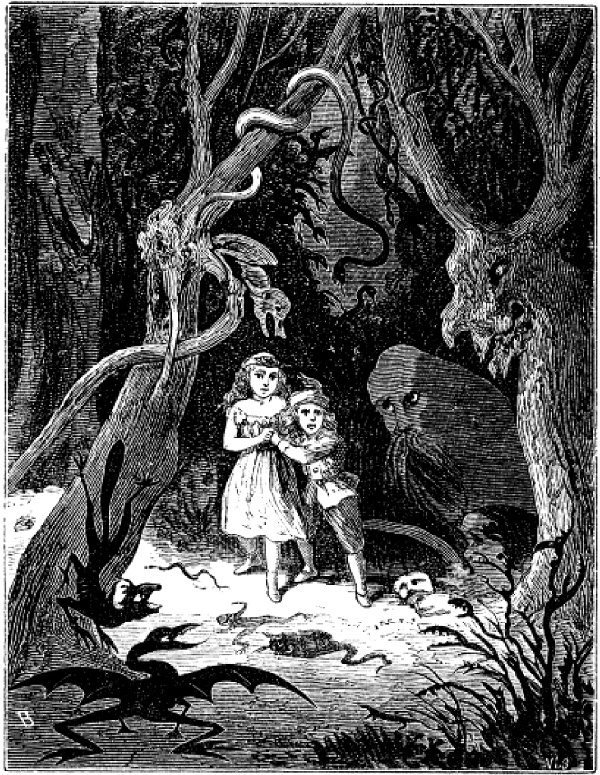

When Eva rises from her sleep, she finds herself in a strange fantasy world called Shadow-Land. In this bizarre new environment of shape-shifting mountains, violets that show her one final memory of her home, and sticks that talk in rhyme, Eva becomes the protector of Aster, the Moon-Prince. She at first believes him to be a doll due to his diminutive, fairy-like size that waxes and wanes aligning with the lunar phases. Aster is woken by Eva’s kiss and explains Eva’s purpose in Shadow-Land. An unnamed and faceless “they” have brought Eva solely to take care of Aster and help him look for his missing white lily flower, which is why he has been temporarily banished from his home. Aster does little to make Eva’s quest any easier—he is stubborn, jealous, possessive, and obstructive. He throws mud at Eva’s white dress, contradicts clues that are meant to help the duo along their journey, is angered by Eva’s memories of home, and strikes Eva in order to run away from her so that he can find his white lily on his own.

As a result, Aster is kidnapped, tortured, and prisoned inside a bird by the Green Frog and her accomplices. Eva must reunite with Aster and meets several unusual creatures along the way that assist her in saving the Moon-Prince, including the children that she plays with in the peaceful Valley of Rest and the Toad-Woman, who supplies Eva with the resources that she needs to trick the Green Frog into relinquishing Aster, a task that involves Eva disguising herself by dying her skin brown. After Eva and the Toad-Woman free him from the body of a bird, the pair at last finds his white lily flower. Aster ultimately admits that he was too proud and angry to accept Eva’s help, which she is able to provide because she is gentle and kind, as he did not want to appear weak. Aster tells Eva that he loves her and kisses her, waking her in the field near her home, where she rejoins her family. The narrator remarks that Eva will always remember her Adventures in Shadow-Land.

Why should this text be recovered?

Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land echoes numerous aspects of Lewis Carroll’s beloved juvenile book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865). During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland inspired a slew of imitations, parodies, and satires (Susina 75). By both nineteenth-century reviewers and modern-day scholars, Nauman’s tale about Eva’s adventures has been written off as a simple imitation of Carroll’s original plot. However, the value of Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land is that setting these texts side by side can unveil a transatlantic literary conversation between the two authors, an Englishman and an American woman, contrasting their attitudes concerning the transition from childhood to adulthood. Despite its problematic association between blackness and servantry, Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land is nonetheless worth recovering. Contrasted by Carroll’s representation of the British monarchy in Wonderland, Nauman’s revision of Wonderland through Shadow-Land is uniquely American in its portrayal of the racial tension deep-rooted in the nation’s culture. Mary D. Nauman transforms Carroll’s British children’s classic into her own by adding distinctive twists and focusing on themes that convey her individual thoughts and feelings about American society.

Although Nauman’s Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land certainly cannot be considered a feminist text as Eva is still limited to the domestic sphere when she is thrust into Shadow-Land, it does celebrate femininity and maintains an interesting stance on masculinity. Eva is consistently gentle and kind to all of the creatures around her, down to the smallest insects. She models unfaltering patience with Aster regardless of his blatant abuse. Throughout the story, she is rewarded, particularly in the form of protection from harm, for her Christlike behavior and compassion towards others.

“So, as ever, Good overcomes Evil, and no service, no matter how small or how trifling it may seem, is ever wasted or thrown away.”

page 62

Meanwhile, Aster is harshly punished for his cruel behavior and must undergo the most significant character development before the end of the story. Through this, Nauman suggests that women are born with these blessed qualities (therefore naturally inclined to be good mothers and wives) and that men should learn to admire and even embody some conventionally feminine characteristics to become better husbands and patriarchs. Nauman reverses the traditional roles of women and men in fairy tales, with Eva being the savior and Aster being the character who needs saving. Unlike Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which concentrates only on the coming-of-age of a young girl, Nauman emphasizes the importance of both boys and girls maturing into adult life and relationships, especially in a direction that encourages future generations of men to treat their wives with a higher degree of love and respect.

“‘But that I—I, a prince,—powerful at home, and only weak now because I had lost such a trifling thing as a flower, should be compelled to ask help of one who was able to help me only because she was gentler and kinder than I was,—I could not do it.'”

pages 157-158

Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land is also notable because it is among the earliest examples of proto-fantasy literature written by an American woman writer. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is one literary work of many that mark the primitive transition from traditional fairy tales into the fantasy genre, which since then has been a field dominated by white male authors and readers, causing female fantasy authors to be neglected and overlooked. Although Carroll often defended the originality of his text, it cannot be denied that he too drew inspiration from his predecessors and his contemporaries (Susina 75). The act of fairy tale writers innovating story elements that were borrowed from one another, like a young protagonist venturing into an alternative world, led to the recognizable tropes of the fantasy genre today. Mary D. Nauman was a contributor to this process. Her creation cannot be dismissed as a mere copy of Carroll’s Wonderland.

References

Bausman, Lottie M. “In Memoriam: Mrs. Mary N. Robinson.” Year Book of the Pennsylvania Federation of Historical Societies and Acts and Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Meeting, Harrisburg Publishing Company, Harrisburg, PA, 1921, p. 147.

“Frederick Robinson (1832-1882).” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14494056/frederick-robinson.

Leonard, John W. Woman’s Who’s Who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of The United States and Canada. The American Commonwealth Company, 1914.

“LTC George Nauman (1802-1863).” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/36402564/george-nauman.

“Mary D. Nauman Robinson (1839-1920).” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14494651/mary-d-robinson.

Meginness, John F. Biographical Annals of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania: Containing Biographical and Genealogical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens and Many of the Early Settlers. Vol. 1, Dalcassian Publishing Company, 1903.

Nauman, Mary D. Eva’s Adventures in Shadow-Land. J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1872.

Robinson, Mary N. “Sidelights on Slavery.” Papers Read Before the Lancaster Historical Society, 5th ed., vol. 15, Lancaster, PA, 1911, pp. 135–141.

Susina, Jan. The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children’s Literature. Routledge, 2010.