Grand Army of the Republic Dedication of the Egg Harbor City Civil War Monument, 1893, in the Egg Harbor City Cemetery. Left to right: ? Guthlein(?), Wm. Hohneisen, Joseph Schwiekerath, F. Waschow, unk., Henry Voss, unk., (STATUE), Capt. Mischlich, Edwin Ertell, Gustave Guenther, John Prasch, Jacob Natter, William Morgenweck, Joseph Engelhardt , Eli Bolling. Image from the collection of the Egg Harbor City Historical Society, used with permission.

On January 1, 1863 President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, tying the Civil War directly to the issue of slavery. Besides declaring freedom for all slaves living within the confines of the Confederacy, Lincoln’s proclamation also allowed African Americans living in both the North and the South to enlist and serve in the Union army. An aggressive recruitment campaign ensued, and within six months the first all-black regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops mustered in at Washington, D.C.

Despite being admitted to the Union army, during their service many black recruits endured added hardships unknown to many of their white counterparts. It was not uncommon, for example, for African American soldiers to receive inferior supplies, perform unappealing tasks ranging from guard duty to manual labor, and to face discrimination from enemies and allies alike. Still, when allowed to fight on the battlefield, observers could rarely deny the bravery, valor, and sacrifice of USCT soldiers.

Heeding the President’s call to arms, several African American men from the Galloway Township area enlisted to serve in the Union army. Among those who signed up at Absecon in January 1864 to serve in Company B of the 25th Infantry Regiment of the United States Colored Troops were brothers Josiah and Charles Boling, their two brothers-in-law James Trusty and Alexander Smith, and Moses Miller. These men went through basic training together at Philadelphia’s Camp William Penn, and subsequently served as privates on garrison duty in Beaufort, NC; New Orleans, LA; and Pensacola, FL during the final two years of the war. Despite not seeing action on the battlefield, the men of the 25th endured the loss of ninety-two fellow soldiers to disease.

Eli Boling, Josiah and Charles’s younger brother, enlisted later, in March 1865, to serve as a private in Company I of the 24th Regiment. Much like his older brothers, Eli performed garrison duty in Washington, D.C. and POW guard duty at Point Lookout, MD during the war’s final year. The 24th also formed part of the occupation forces at Richmond and Burkeville, VA after the war. During his time of service, Eli befriended an Egg Harbor Township resident by the name of William H. Lee, who ultimately became his neighbor after the war. All of these men were mustered out of their respective regiments in 1865 and subsequently returned to their homes.

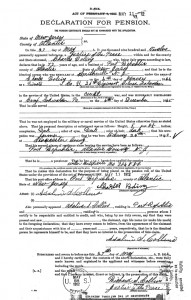

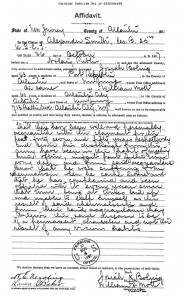

Although the federal military pension laws passed by Congress were neutral on the issue of race, fewer African American Civil War veterans won pension claims than their white counterparts. This was primarily due to the prevailing racism, illiteracy, and poverty experienced by blacks of the era, since such claims required both money and certain documentary evidence, such as birth and marriage records, that some black applicants could not supply. Still, federal pensions provided a great source of financial assistance to eligible veterans and their families.

Five men from the Boling Settlement—Eli Boling, William H. Lee, Alexander Smith, James Trusty, and Moses Miller—applied for federal military pensions between 1888 and 1897, and all but Moses Miller received them. After Congress passed the Dependent Pension Act of 1890, widows of Union veterans could also apply for such financial assistance. Annetta Mott, Rosella Smith Boling, and Anna Trusty Boling—the respective wives of Eli Boling, Josiah Boling, and Charles Boling—therefore applied for, and received, military pensions after the deaths of their husbands.