What makes poetry? Is it the words or the ideas? Is it what you see, what you hear? Or is poetry the thing you feel when you read it?

The answer: it can be all those things. Subjective and personal by nature, no two people are likely to experience a poem in exactly the same way – that makes defining it in absolute terms somewhat complicated. However, there are certain basic elements necessary in order to make a piece of writing poetic. Prose broken up into bite-size pieces, fancy spacing and all, is still prose; without things like meter, form, and rhyme, the poetry of an idea can sometimes get lost in the middle of all those words.

The trick is striking the right balance between recognition and readability. Just as disregarding all standard conventions can produce a less than poetic finished product, overusing them can have precisely the same effect.

* * * * *

In Beginning Again and Other Poems, J.W. Stanistreet uses the technique of rhyming a good deal. His “A Morning Thought” manages to employ it just about perfectly because he resists the urge to beat the reader over the head with it. His style is subtle and a little bit whimsical, as is his formatting; it is laid out interestingly without being a standard form poem.

Conversely, James Lane Pennypacker’s “Acrostic,” Ted Brohl’s “haiku,” and P. Mortimer Lewis III’s “My Prayer” all choose to embrace the idea of a standard form as opposed to dancing around it. Two out of three, “Acrostic” and “haiku,” bear the name of their form and capitalize on the fact that they are visibly recognizable. “My Prayer” has less first-glance obviousness, but its content clearly marks it as an ode; Lewis is glorifying God and all the nature he created.

* * * * *

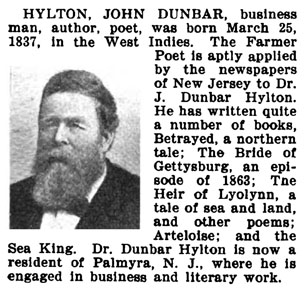

J. Dunbar Hylton, a doctor by trade, also tries his hand at an ode in Above the Grave. “Lost” speaks glowingly of a beloved Ellenore, but the most striking element of this poem is not its form nor its rhyme, but its meter. Concentrating on the stressing of syllables, he expertly alternates between lines of iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter. Yet even with his level of skill the effect is heavy-handed and repetitive, proof that you sometimes can have too much of a good thing.

There is no formula for writing the perfect poem. There is, however, some method behind the creative madness – meter, form, and rhyme are simply manifestations of that method. They don’t create a poem, but they do help us start to define it. Because while the elements that make something poetic may be universal, poetry will always be in the eye of the beholder.

Brohl, Ted. “haiku.” Ted Brohl’s Gargoyles and Other Muses. New York: Vantage Press, 1990.

Hylton, J. Dunbar, M.D. “Lost.” Above the Grave of John Odenswurge, a Cosmopolite. New York: Howard Challen; Palmyra, NJ: the author 1884.

Lewis, P. Mortimer, III. “My Prayer.” The Water Lily and Other Poems. Norristown, Pa.: The Norristown Press, 1929.

Pennypacker, James Lane. “Acrostic.” Verse and Prose of James Lane Pennypacker. Haddonfield, New Jersey: The Historical Society of Haddon-field, 1936.

Stanistreet, J. W. “A Morning Thought.” Beginning Again and Other Poems. Hammonton, N.J.: Privately printed by J. W. Stanistreet, 1933.